Home

Artists

Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter’s artistic explorations, which stretch over more than six decades, constitute a radical attempt to integrate representation and abstraction. Known for his painted copies of black and white photographs rendered with a blurred effect, Richter has broadened the potentials of both photography and painting.

Interested in Gerhard Richter?

15:48

Gerhard Richter: Drawings

‘The drawings are traces of a life, creating territories in relation to limits and potentials. Communications transmitted to whoever will regard them.’ — Prof. Michael Newman

12:00

Gerhard Richter: Doubt

‘He disturbed my sense of what art should be.’ — Robert Storr on Gerhard Richter

1:19

1 Minute 1 Work: Gerhard Richter, Ema (Nude on a Staircase), 1966

Writer Robert Storr examines Gerhard Richter’s ‘dissenting’ painting ‘Ema (Nude on a Staircase)’.

11:49

Reflecting on Gerhard Richter

An exploration of the processes of leading artist Gerhard Richter as presented through his glass sculptures and paintings.

HENI Publishing · 23 Sep 2023

The Richter Interviews – Hans Ulrich Obrist

The Richter Interviews collects a series of conversations between Hans Ulrich Obrist and Gerhard Richter over two decades of discussion and collaboration.

HENI Publishing, HENI Talks · 01 Sep 2021

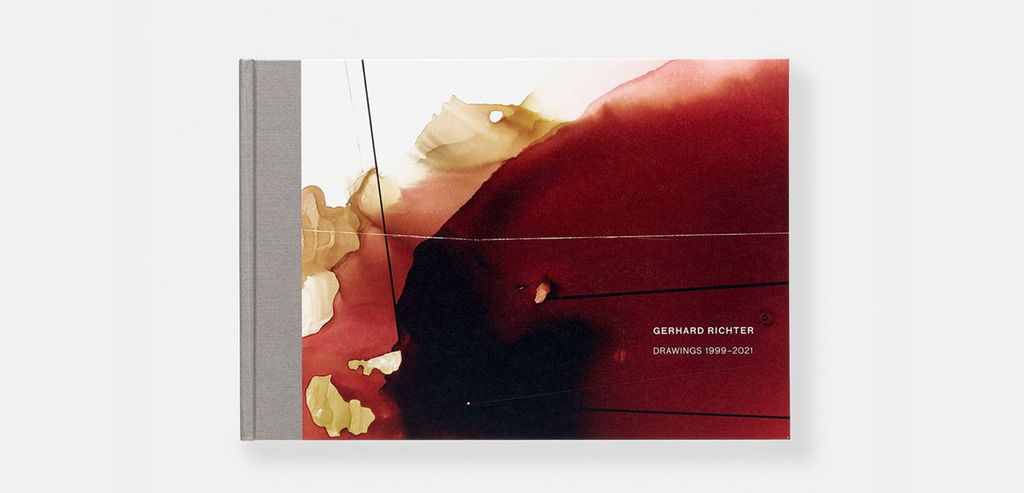

Drawings 1999-2021 – Gerhard Richter

Dive into an exclusive collection of 80 rare graphite and ink works by Gerhard Richter, crafted meticulously between 1999 to 2021.

HENI Editions · 30 Nov 2020

Gerhard Richter – Cage Prints

HENI Editions is delighted to announce six new limited-edition prints with Gerhard Richter, based on Richter’s monumental 'Cage' paintings.

About the Artist

Gerhard Richter’s artistic explorations, which stretch over more than six decades, constitute a radical attempt to integrate representation and abstraction. Best known for his painted copies of black and white photographs rendered with a blurred effect, Richter has broadened the potentials of both photography and painting.

Born 1932 in Dresden, Germany, Richter’s childhood was affected by the rise of the Nazi regime and the traumatic events of World War II. According to some of his critics, these painful memories, combined with a regimented life in East Germany under Soviet rule, discouraged him from conveying ideological expressions through art. Such unpretentious perspective materialises in his continued focus on colour combinations and on the tangible quality of his canvases.

Richter began his studies at the Dresden Art Academy in 1951, but disliked their dogmatic emphasis on Social Realist art. In 1961, Richter fled to West Germany where he studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. In this liberated, experimental environment, Richter first produced his photopaintings.

Richter admits Pop Art gave him the license to use photography in his photopaintings. Like Warhol, he saw in photography’s mechanical recording a way to build a machine-like aesthetic that denied artistic involvement. Sourcing photographs from family albums, newspapers and magazines, Richter was interested in the photograph’s status as reproduction, as one stage removed from reality. The photopaintings function like echoes of distant worlds. This dissociation from the subject was developed in his signature blur, created by running a dry brush through the wet paint. In the photopaintings of his family, these distancing effects resonate a sense of confusion of how to make sense of their difficult history.

Richter advanced this dissociative language in his printmaking practice. From his early editions, such as ‘Dogs’ (1965), to the 2017 Giclée print of ‘Tulips’ (1995) the artist employs the medium as an extra layer of aesthetic distance, being based off a painted image. At the same time, the print completes the work’s cycle, which started with a photographic image that was abstracted in paint and ended with the painted image returned to its photographic state.

Alongside his photopaintings, Richter has developed new possibilities for abstract art which build on his aesthetic of non-involvement. The first abstract series ‘Colour Charts’ (1966) was based on paint charts found in hardware stores and reproduce their geometric grids of colour. Later geometric abstractions used a random computer-generated selection to arrange colours by chance. One of his most intricate, ‘4096 colours’ (1974) would inform the design of Richter’s monumental stained glass windows for the south transept of the Cathedral of Cologne (2007).

Unwilling to stick to one genre, in his ‘Works Behind Glass’ (2008-10) Richter embraced a free form abstraction. In these, poured enamel paint is squelched flat between glass sheets. Recreated as print editions, the Diasec-mounted chromogenic print on aluminium brilliantly captures the harsh flattening effects of the glass; indeed, the flattening becomes more extreme in the print as the layers of physical paint are less distinguishable. The spectator is invited to abandon themselves to the Dionysian swirls of paint.

The diversity of Richter’s oeuvre is remarkable, but equally extraordinary is the consistency of his vision. Throughout his work, he promotes an art that denies artistic involvement. Through this, Richter lays bare a natural beauty: from his tender and diffuse early photopaintings to the vibrant exaltation of colour in his glass paintings.