Home

Artists

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon’s raw images of abject bodily distortions seem to answer the Surrealist Andre Breton’s call for a ‘convulsive beauty’. The figures that populate his paintings express not only the collective cultural anxieties of post-war Europe, but also his intimate emotional struggles.

Interested in Francis Bacon?

HENI Art Club · 06 Apr 2022

The Francis Bacon Catalogue Raisonné is now available on HENI Art Club

HENI Art Club now holds exclusive access to the Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné, presenting the entire collection in digital form as a free ebook.

HENI Art Club · 08 Feb 2022

Bacon in Moscow – James Birch

Join HENI Art Club for an exclusive conversation with curator James Birch about his memoir 'Bacon in Moscow' and his ground-breaking 1988 exhibition.

HENI Publishing · 28 Jun 2016

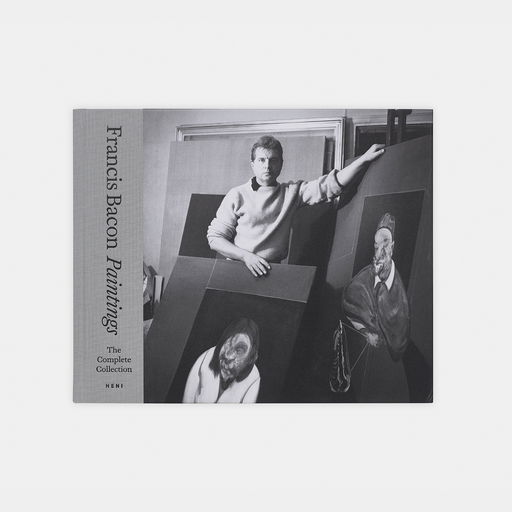

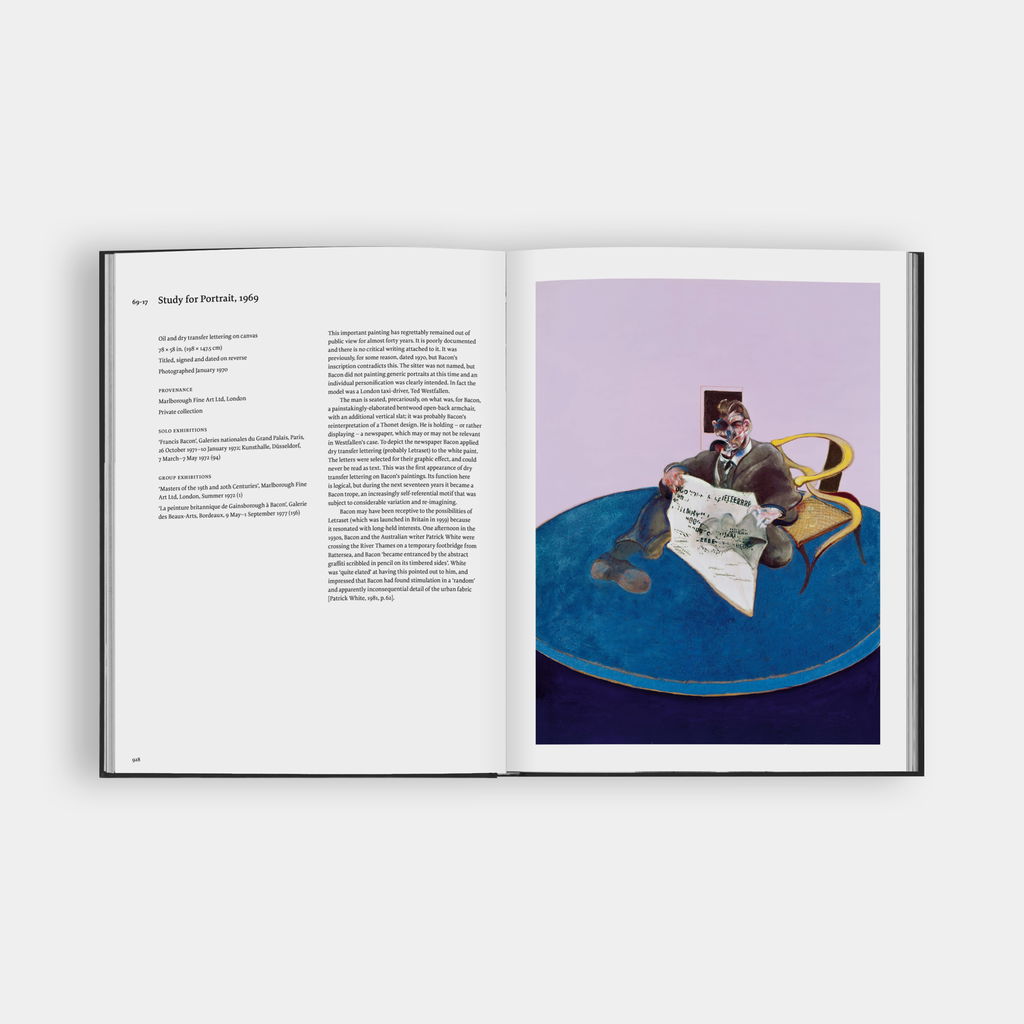

Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné

This landmark publishing event presents the entire oeuvre of Bacon’s paintings for the first time in a deluxe five-volume boxed set.

About the Artist

Francis Bacon’s raw images of abject bodily distortions seem to answer the Surrealist Andre Breton’s call for a ‘convulsive beauty’. The figures that populate his paintings express not only the collective cultural anxieties of post-war Europe, but also his intimate emotional struggles.

Bacon was born in 1909 in Ireland to middle class English parents. At age 16, he was allegedly discovered by his horrified father dressed in his mother’s underwear, a traumatic event that remained with him for the rest of his life. Before settling in London in 1926 with no formal art training, Bacon travelled to Berlin, and later visited Paris. Here, he became interested in Picasso’s biomorphic renderings of the human form, which inspired his understanding of the human body as a permeable, malleable matter. His work ‘Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion’ (1944) shows part-human, part-animal figures in agonised contortions, with grotesque details like open, toothy mouths and pithy, angular ribs.

Bacon was drawn to popular culture and collected shocking news and documentary images. He obsessively watched Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film ‘Battleship Potëmkin’, his fascination with the close-up footage of the nurse covered in blood and silently crying out eventually inspiring his screaming figures. In ‘Study After Velázquez’ (1950), based on Diego Velázquez’s ‘Portrait of Innocent X’ (1650), the pope screams out while he clenches the arms of his throne. Bacon’s conflating of popular imagery and traditional art is what makes his figures so human and intensely vulnerable.

From the 1940s Bacon started isolating his figures in nightmarish, cage-like boxes and circular metal rails. As they seal the figure into their own world, these ‘spaceframes’ resonate Friedrich Nietzsche’s description of the ’wretched glass capsule of the human individual’.

By the late 1950s Bacon’s reputation was international, later elevating it in 1962 with his influential ‘Three Studies for a Crucifixion’. He was also becoming known for his radical portraits of his friends, surrounding them with only a few elements like a bed or a rug or isolating their busts against a solid background. The clarity of the background plays against the treatment of the figure, which violently decomposes the sitter’s identity in painterly brushstrokes. ‘In Memory of George Dyer’ (1971) immortalises the memory of Bacon’s former lover who committed suicide, depicting Dyer multiple times in a frenetic attempt to make his presence real.

Bacon produced enigmatic, theoretical landscapes along the way, but never abandoned his explorations of the human body. He progressively reduced it to parts and even residues, employing new techniques to expand the communicative potential of his images. For example, he experimented with spray paint, which produces a tactile, granular surface suggestive of physical traumas such as bruises or cuts. He also sullied his images by adding sand and dust onto his canvas or sometimes a final spurt of white paint to suggest bodily fluids. However, Bacon liked this scatological texture sealed, preferring his canvas framed behind glass.

Bacon said he strove to represent ’the brutality of fact’, which is reflected in the pulsating energy of his grotesque forms which contain life and death. As his figures scream out, teeter on edge of a metal rail, or are contained in a cage, they reverberate the pain and alienation of modern experience.